Sara was to be married

– at the age of seven

She is one of millions of

children around the world

who have been forced

to flee their homes.

War and conflict are hitting children hard. Children living with conflict and poverty are at greater risk of experiencing abuse.

Right now, around 40 million of the world’s children are displaced.

In Afghanistan, Sara was supposed to be married when she was seven. But she fled.

The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) helps women and girls forced to flee in Afghanistan. Support our work today.

“What do I remember about Dad? Just how he looked: he was very tall and had long hair,” says Sara. She’s sitting at a café table, speaking in a low voice.

“I don’t remember the day when I realised that we would never see him again. Maybe because I was used to him being away a lot – he was a long-haul driver. Maybe I remember so little because I was only seven years old at the time.”

Norway is where she, her three sisters and her mother finally ended up in 2012. Sara was nine years old. Their journey took about 40 days. It was arranged by people smugglers, and the small family had no idea where they would end up. They could only hope that it would be a safe country in Europe.

Sara looks down at her hands in her lap:

“We’ll never know what happened to Dad. It could be he was stopped by the Taliban. His job was to transport carpets between Afghanistan and Pakistan,” she continues.

She straightens up a little in her chair and says with a small sigh:

“So Mum was left alone with us four girls.”

“We were seen as defenceless girls”

Sara chose to tell her story to the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) because she wants the world to know that half of all displaced people are in fact children and young people under the age of 18. In 2019, this amounted to around 40 million children.

“The fact that Dad disappeared… Without Dad – the man in the family – we had no protection and were seen as defenceless girls,” says Sara.

Her original homeland, Afghanistan, has a very young population. Around 40 per cent are under 15 years old.

Many remember the Afghan girl Sharbat Gula, whose portrait was taken by the American photographer Steve McCurry for National Geographic magazine.

Who can forget the young face with the intense green-eyed stare? An iconic photo taken in 1985. The photograph became a symbol of the influx of refugees that came in the wake of the Afghan-Soviet war, which lasted from 1979 to 1989.

In recent years, the mass media has shown other images from Afghanistan. Images of conflict, war and destruction. Images of poverty.

Around 40 per cent of the Afghan population today lives below the poverty line, and three out of ten suffer from malnutrition. Poverty is also one of the reasons why many girls are married off while they are still children.

A young girl is selling cheap bangles in a camp for displaced people, Kabul. Photo: Janus Engel Rasmussen/Scanpix

A young girl is selling cheap bangles in a camp for displaced people, Kabul. Photo: Janus Engel Rasmussen/Scanpix

A boy plants a tree in Afghanistan’s barren soil. Photo: Jim Huylebroek/NRC

A boy plants a tree in Afghanistan’s barren soil. Photo: Jim Huylebroek/NRC

“War violates the rights of all children – the right to life, the right to family unity, the right to health, the right to personal development and the right to protection.”

These are the words of Graça Machel in the ground-breaking UN report “The Impact of Armed Conflict on Children”, which was published back in 1996.

In this report, she made a number of suggestions for how the UN and the international community could improve the situation for children living through conflict.

Twenty-four years later, there is still a massive gap between politicians’ statements at international conferences and the reality in conflict-stricken areas.

Poverty and stigma

“When Dad disappeared, some of our family wanted to marry us off. But Mum didn’t want to,” says Sara.

In Afghanistan, not getting married can be a big problem. It can also be risky to wait too long before marriage.

Financial considerations are an important factor in why girls around the world are married off at a young age. The family gets a bride price and one less mouth to feed.

In some Afghan communities, not being married at a young age can also be associated with stigma. People may wonder why a girl isn’t married and this makes her an outsider.

There is also a perception in Afghanistan that married women are safer than unmarried women. And if a woman gets married, her biological family doesn’t have to be responsible if a situation arises where questions are asked about the woman’s “purity”.

Read more: “We demand our rights!”

Child marriage is a consequence of poverty and weak legislation as well as culture and tradition.

It is a global problem and one of the biggest obstacles to education and equality for girls and boys – and to development in poor countries.

Every year, 12 million girls under the age of 18 are married off, according to UNICEF. While this is a global problem, most of the girls affected by child marriage come from South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Traditionally in Afghanistan, the man’s family takes the initiative for a marriage. The woman’s family is not in a position where they can take the initiative with respect to potential marriage candidates.

“They wanted to marry me to an adult man who was a distant relative because Dad was not around anymore and could no longer take care of us,” Sara continues, defiance shining in her big, brown eyes.

A dangerous childhood

Sara lifts her glass and takes a sip of her soda. She puts it down and continues:

“My mother grew up surrounded by war. Among other things, she and her family had to live in a tunnel for a while to escape the rockets.

“As a child, I wasn’t allowed to play outside. I remember the adults talking about all the dangers we had to watch out for, like being kidnapped, for example. I also remember the panic on their faces when bombs went off near where we lived.”

Sara and her sister Laila are playing with a water fountain. They have just arrived in Oslo and are living in an asylum centre. Photo: Private

Sara and her sister Laila are playing with a water fountain. They have just arrived in Oslo and are living in an asylum centre. Photo: Private

Assad Souri School for displaced children in Kandahar, Afghanistan, has been attacked and occupied several times by both sides in the conflict. Photo: Becky Bakr Abdulla/NRC

Assad Souri School for displaced children in Kandahar, Afghanistan, has been attacked and occupied several times by both sides in the conflict. Photo: Becky Bakr Abdulla/NRC

About half of all those fleeing violence and armed conflict are children under the age of 18.

In 2019, they numbered 40 million. This is almost double the number of children who were displaced in 2010.

Many boys are killed, abducted, recruited into armed groups or maimed. Boys are also at risk of sexual violence, but girls are at an even greater risk of being the victims of sexual violence.

“But I feel that the main reason why Mum chose to take us and flee alone, was that we no longer had a man to take care of us,” Sara reflects.

“When we left, Dad had been gone for two years.”

A hopeless situation

“My mum’s name is Solha. It means ‘peace’ in Pashto, our language. She got that name because her parents wanted her to bring peace to Afghanistan,” says Sara.

She explains that her mother sold everything she had of value: the gold jewellery from her wedding and the small piece of land she owned, which she had received from her parents before she got married.

“By Western standards, Mum was still a young woman when Dad disappeared, just 30 years old. If she had remarried so as to have a man who could protect us, she would probably have been looked down on. That’s just the way it is in Afghanistan.

“Another thing is that we didn’t know what had happened to my dad. If Mum had married someone else, people would probably have started saying that she should’ve waited for him.”

Risking everything

Sara’s mother sought out one of her husband’s acquaintances, who she had heard could help her escape: a people smuggler. She was taking a great risk.

“But it was our only chance. Think about it: Mum gave him all her money. Absolutely everything we owned! She had no guarantee that he wouldn’t run away with everything. She could only hope that she could trust him.”

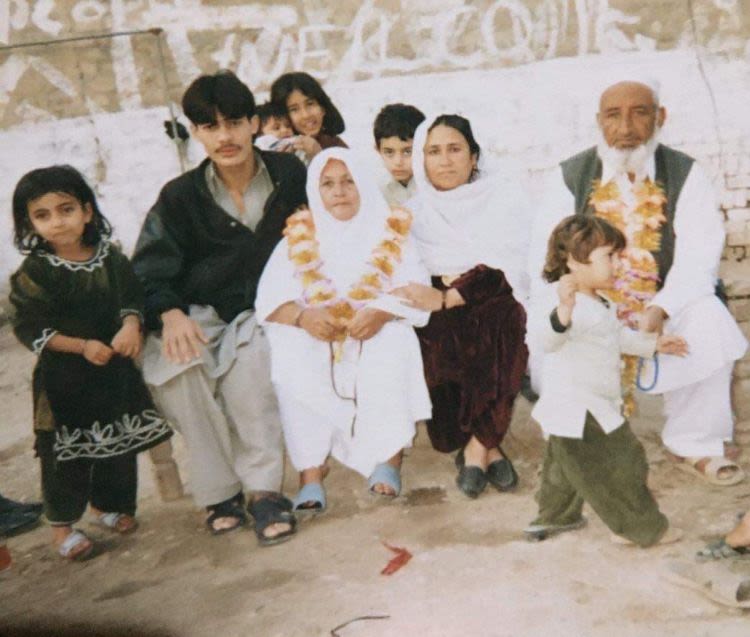

A special day in Afghanistan: Sara’s grandparents have been on a pilgrimage to Mecca and the family is gathered for a celebration. Sara is at the front of the picture. Photo: Private

A special day in Afghanistan: Sara’s grandparents have been on a pilgrimage to Mecca and the family is gathered for a celebration. Sara is at the front of the picture. Photo: Private

"My family put all their money together so I could get out. If I reach Europe, at least there is a chance of a future," says Abdul Khaliq, 14, from Kabul. Photo: Jim Huylebroek/NRC

"My family put all their money together so I could get out. If I reach Europe, at least there is a chance of a future," says Abdul Khaliq, 14, from Kabul. Photo: Jim Huylebroek/NRC

Every fifth child in the world – that’s 415 million children – lives in areas affected by war and conflict.

Serious child abuse is on the rise. Sexual abuse is used as a weapon of repression in some countries, including Afghanistan, Somalia, Myanmar and Sudan.

Between 2005 and 2018, almost 20,000 cases of sexual violence against children were reported, according to Save the Children, a number that is believed to be just the tip of the iceberg.

Sara smiles:

“Mum said to the man: ‘Help my daughters and me to Landan.’ Yes, she said ‘Landan’. You know, it doesn’t even sound like ‘London’. But that’s what Afghans call Europe: Landan,” she says.

“The man replied: ‘I’m sending you to a place where you’ll have a better life.’”

Sara shakes her head:

“Today, I can easily imagine how scared and uncertain my mother must have felt in that situation. All her life, she had learnt that it was not safe for girls to be with strangers.

“She had been told that she had to protect herself from men. Now she had to trust that this strange man and his partners – men she knew nothing about – would take care of us.”

Long journey to freedom

They travelled in a large group – both adults and children. First, they crossed the border into Pakistan. Then, they went on to Kuwait, Iran and finally Europe.

This is what Sara remembers from the escape:

“There was one man in particular who was very strict. He kept saying we had to be quiet.

“We had to walk a lot. Even over mountains. I stepped on things that were disgusting or that hurt. Several young Afghan boys were travelling alone in the group. They helped my mother a lot, including by carrying us.”

In 2018, at least 12,125 children were killed or injured in war, a 13 per cent increase from the previous year.

In the same year, 1,892 attacks on schools and hospitals were registered, which is an increase of 32 per cent from the previous year.

Children are not just targets, they are often also forced to carry out acts of violence.

“I remember very clearly that we sat in lorries. It was no fun. The trailers were full and cramped. We had to be completely silent so we wouldn’t be discovered by the police.

“The worst thing was that we had very little to eat. Occasionally, we had some biscuits and a little water. It was terrible being so hungry all the time. Once, we were in a lorry full of watermelons. We didn’t have a knife, so we had to smash two watermelons against each other to open them so we could have something to eat.

“You know, when you’re hungry and you have to go so far – it’s a nightmare. But we got used to that in a way, too. It also helped that there were a lot of children traveling together, that we were all in it together.

“We took boats, too. Inflatable boats. Fishing boats. Then we had to sit very still and not move. There were a lot of people in the boat and everyone had to keep their balance so that it wouldn’t tip over.

“I remember I was scared a lot. But I was raised to be careful.

“First and foremost, I was determined to survive.”

A new life

Today, Sara goes to school. She also has two jobs. In addition, she travels around and gives lectures on youth for a non-profit foundation.

She smiles:

“Naturally, I still have contact with some of my family in Afghanistan – aunts, my grandmother and a cousin.

“My cousin is my age. She dropped out of school to get married. I can’t blame her, though. For her, it was natural. But I tell her: ‘You can go to school even though you’re married. You can be something, get a job.’ But for her, it’s not an option.”

Sara lets out a small laugh:

“Maybe my cousin thinks that I’m really just hanging around in Landan, waiting to get married.”

Sara has big plans for the future. She wants to be a social worker. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Sara has big plans for the future. She wants to be a social worker. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

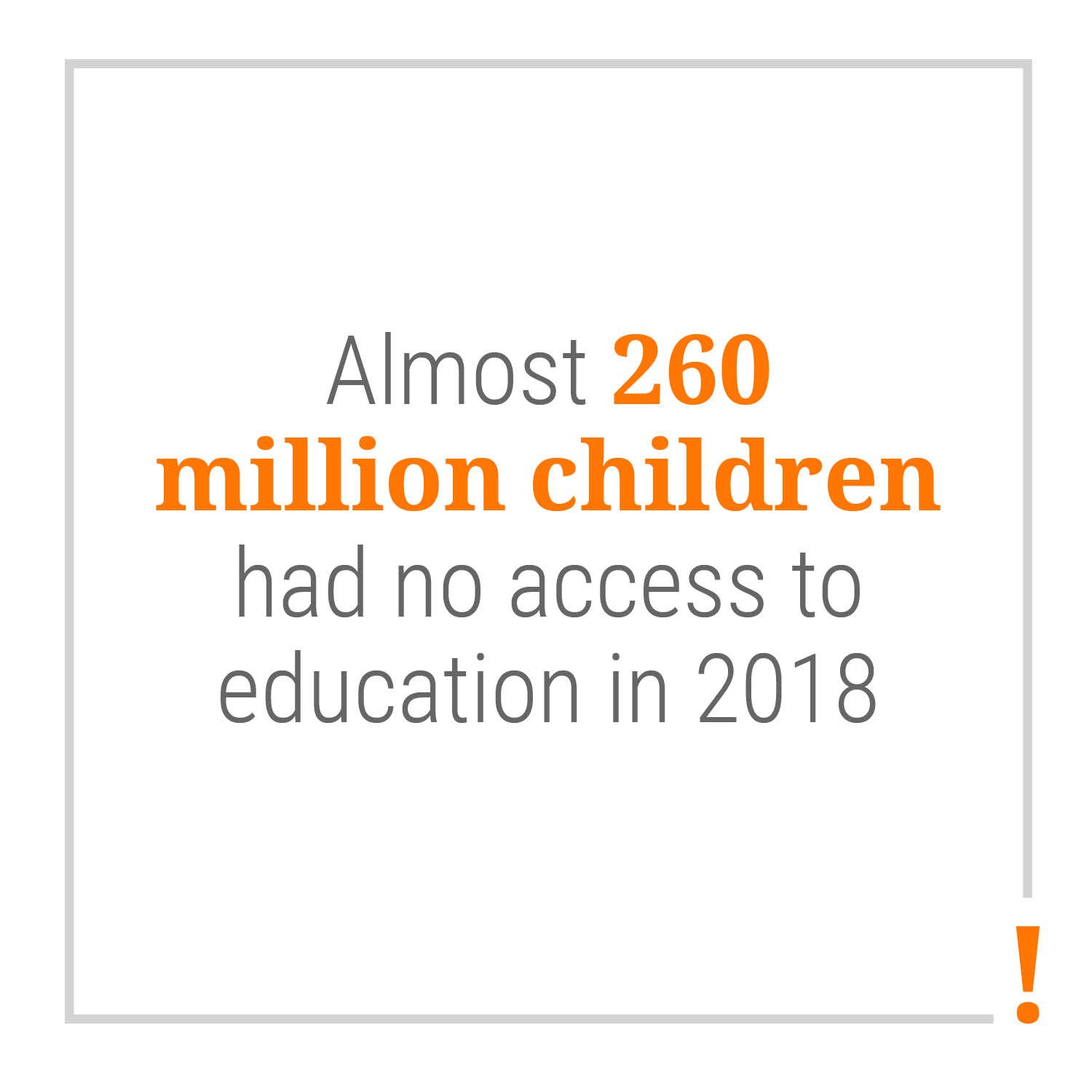

In 2018, around 260 million children were without access to education, according to a UN report, which indicates that the situation is deteriorating due to the coronavirus crisis.

Most of the children who can’t go to school live in South and Central Asia, as well as in sub-Saharan Africa.

Then she becomes serious:

“I have dreams and opportunities. I want to become a social worker and help others. I want to be a voice for girls and refugees who are having a hard time – to help those who haven’t been as lucky as me.

“I will go back to visit Afghanistan one day, though it might not be for a long time.

“I want to see the beautiful nature, taste the good food and experience the wonderful culture.”

Education gives girls and boys a future. Girls who do not have access to education are at greater risk of being married off. Here at the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), we work to ensure that girls have the opportunity to stay in school.

Schools can provide children with protection and stability as well as knowledge and skills. One of NRC’s most important tasks is to ensure that children and young people can keep learning, even in times of crisis.

“I’m not talking about culture as oppression and war. But about music, dance and good traditions.

“I remember that even though there was a lot of violence on TV in Afghanistan, there was a special channel with music that was often on at home. It was Grandma who used to put it on.

“Then we would dance. We still do. I love to dance. Everything from Bollywood dances and traditional Afghan dancing, to hip hop and street dance.

“That is the good culture I will remember from Afghanistan,” says Sara.

“That is what I will bring with me into the future.”

Girls, who are part of the Afghan Mobile Mini Circus for Children (MMCC), participate in a juggling competition in Kabul, in 2015. Photo: Reuters/Scanpix

Girls, who are part of the Afghan Mobile Mini Circus for Children (MMCC), participate in a juggling competition in Kabul, in 2015. Photo: Reuters/Scanpix

Making faces is fun! Sara and her sisters are gathered in front of the camera. From the left: Laila, Hila, Rokhsar (wearing hijab) and Sara. Photo: Private

Making faces is fun! Sara and her sisters are gathered in front of the camera. From the left: Laila, Hila, Rokhsar (wearing hijab) and Sara. Photo: Private

Sara loves to dance. “Colour Games” is a Norwegian foundation that works to bring cultures together and exchange artistic ideas. “In this video I am dancing with Victoria. She taught me hip hop, I taught her Bollywood dance,” says Sara.

Sara loves to dance. “Colour Games” is a Norwegian foundation that works to bring cultures together and exchange artistic ideas. “In this video I am dancing with Victoria. She taught me hip hop, I taught her Bollywood dance,” says Sara.

What does NRC do?

The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is a Norwegian organisation that helps people forced to flee in over 30 countries around the world.

UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, has an agreement with NRC to ensure rapid assistance to refugees – including children – in times of crisis.

Among other things, we contribute to providing children, young people and adults with food, shelter, legal aid and education. An important task is to defend the rights of displaced people. Another is to reach out with help where the need is greatest.

Read more about our work with children who have been forced to flee

Sources for this article

The international report, “Stop the War on Children – Gender Matters” from Save the Children 2020; NRC's Global Displacement Overview; Aftenposten; Bistandsaktuelt (Development Update); the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia; NORAD; Spor arkeologi og kulturhistorie no. 1 2012; The Norwegian Immigration Service’s specialist unit for country information; Memorandum on marriage in Afghanistan, 1 May 2019, Plan International