Her er fem ting du bør vite om konflikten i Ukraina:

#1 Trosser farer for å se familien

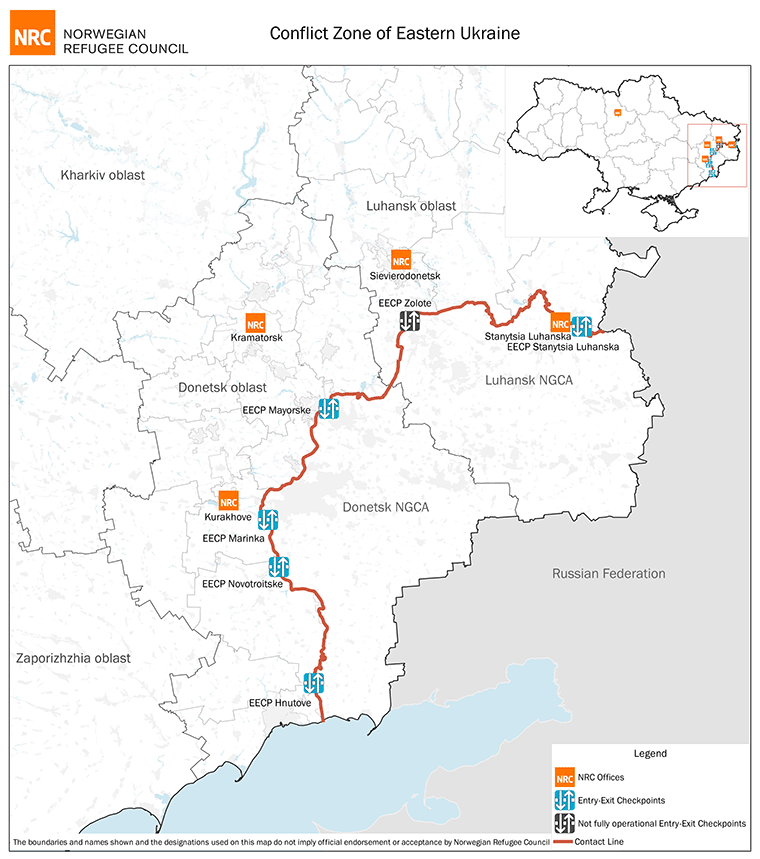

I april 2014 brøt det ut konflikt øst i Ukraina, som siden har vært delt i to: på den ene siden regjerer myndighetene og på den andre regjerer ikke-statlige grupper. Det som tidligere var ett samfunn er nå splittet av en grense lenger enn avstanden mellom Oslo og Stockholm. Langs den minelagte frontlinjen står fareskiltene tett i tett og advarer mot udetonerte eksplosiver, og ved de fem kontrollpostene deler piggtrådgjerder grensa i to.

Hver måned krysser rundt 1,1 millioner ukrainere frontlinjen. De trosser farer som bomber og landminer og risikerer livet for å besøke familie som bor på den andre siden, handle på markedet, skaffe viktige dokumenter eller oppsøke offentlige tjenester som helsehjelp.

Folk står i kø ved kontrollpostene i timevis, gjennom den kalde vinteren eller under stekende sol i sommermånedene. De fleste kontrollpostene mangler tilgang til drikkevann, toaletter og førstehjelp.

#2 Over 3.300 sivile drept

Konflikten rammer sivilbefolkningen hardt. Over 3.300 har blitt drept og rundt 9.000 skadet siden den brøt ut i 2014. Over 50.000 boliger på begge sider av kontaktlinjen har blitt skadet eller ødelagt, i tillegg til skoler, sykehus og vannanlegg.

Fem år med kamper har etterlatt udetonerte eksplosiver spredt over enorme områder i konfliktsonen. Dette utgjør en stor fare for sivilbefolkningen, inkludert en halv million barn som bor ved frontlinjen. Det begrenser tilgangen deres til markeder og helsehjelp, og muligheten for å drive landbruk og sanke ved.

Ukraina er ett av landene i verden med flest dødsfall som følge av landminer og udetonerte eksplosiver. Siden begynnelsen av konflikten har det blitt registrert 924 dødsfall som følge av miner og udetonerte eksplosiver.

#3 Må ta umulige valg

Den vedvarende krisen har strukket folks ressurser til det ytterste. Familier har mistet levebrødet og ser ingen annen utvei enn å selge eiendelene sine og kutte drastisk ned på utgifter.

Den økonomiske nedgangen og høye arbeidsledigheten i denne delen av landet tvinger innbyggerne øst i Ukraina til å ta umulige valg, som å velge mellom å kjøpe mat, medisiner eller sende barna på skolen.

Dårlige sosiale tjenester og manglende tilgang til markedet rammer de mest utsatte, som eldre, enslige foreldre og folk med funksjonsnedsettelse. Over en million mennesker, inkludert folk som har flyktet fra hjemmene sine, har ikke tilstrekkelig tilgang til mat og trenger hjelp til å forsørge seg.

#4 Mangler full tilgang til rettigheter

Konfliktrammede i Øst-Ukraina har ikke full tilgang til rettighetene sine.

Nesten 700.000 pensjonister mottar ikke pensjonene sine fordi konfliktrammede må registrere seg som internt fordrevne for å få utbetalt denne. Mange har pensjonen som eneste inntektskilde, men får utbetalt denne helt vilkårlig.

I områdene rundt regionene Donetsk og Luhansk, som kontrolleres av ikke-statlige grupper, mangler rundt 60 prosent av barna fødselsattester som er utstedt av ukrainske myndigheter. Nærmere 80 prosent av dødsfall i disse områdene blir ikke registrert av ukrainske myndigheter.

#5 Usikre fremtidutsikter

Man regner med at rundt en million mennesker har blitt fordrevet på permanent grunnlag.

Ukrainere som har måttet flykte fra hjemmene sine på grunn av konflikten har behov for å kunne gjenoppta et normalt liv, enten ved å vende hjem frivillig, eller ved å integrere seg på et nytt sted.

Mennesker som lever på flukt over lang tid, opplever ofte at det er vanskelig å integrere seg i vertssamfunn med knappe ressurser. Mange familier på flukt opplever diskriminering og vanskeligheter knyttet til å finne bolig, få tilgang til tjenester og skaffe fast inntekt. Mange steder får ikke internt fordrevne stemme ved lokalvalg, noe som bidrar til å hindre integrering.